Late-Stage Fandom Is Following Your Faves off a Cliff

welcome to strong feelings! Essays by writers we love, in which they share their most impassioned opinions on a given subject. In today’s strong feelings, writer & social video producer for mixed feelings, Catherine Mhloyi explores blurry lines between love and hate and the long history of queer-coding archenemies.

“You’re a fake fan!” my coworker joked as we discussed my notable disinterest in Taylor Swift’s podcast appearance debuting her new album and my failure to retain the date of its release. As someone who begrudgingly embraced my classification as a “Swiftie” after traveling to another state to snag last minute tickets to the Eras tour, I did feel a bit like a phony. I told them that The Tortured Poets Department “broke my heart,” which wasn’t entirely hyperbolic because that’s how close I had gotten to her music and inevitably her as an artist. The fact that TTPD was sonically offensive and a third of the songs were about her racist ex-boyfriend (had I not known that I probably would’ve enjoyed the album more) gutted me.

It was last week after The Life of a Showgirl proved to be her most poorly written, thematically vapid, and woefully unrelatable album (IMO) that I finally realized that it’s okay to hate Taylor’s new stuff just as much as I love her old work — no one will kick my ass IRL, and to disengage from any interest in her personal life wouldn’t diminish my connection to her earlier repertoire. No celebrity is deserving of this level of devotion, especially since these billionaires are high-key evil, but how do we know when it’s time to un-stan?

Fandom, or being a stan, has changed significantly over the years, which is largely credited to the existence of social media and the way that celebrities engage with it. It’s funny because the term “stan” comes from the Eminem song with the same name released in 2000, almost a decade before the widespread use of Twitter and Tumblr (the platforms most associated with fan accounts and celebrity interactions). Stan, the subject of the song, was a fictional, obsessive fan whose correspondence with “Slim [Shady]” was entirely through unanswered letters and one last desperate cassette tape.

Lyrics like “I just think it’s fucked up you don’t answer fans,” and Eminem’s ultimate response, “I’m glad I inspire you, but, Stan why are you so mad?” really encapsulate today’s relationships between fans and artists. But they are no longer investigated as, or associated with, erotomania, especially now that many of these stars feed into it and even depend on it, e.g., I left these easter eggs especially for you, this diss track is awesome because you hate that person as much as I do, you are the reason I’m so successful, thank you, I couldn’t have done it without you.

The more we have access to our favorite artists’ thoughts, feelings, and personal lives, the more we start to lump that in with their art. But what happens when the art no longer measures up? What if the music’s still good, but your fave is a horrible person? Some of us devote years of our lives and entire social media accounts to our idols, which is probably why it’s hard to let go, even when that artist has veered so far from who they were and what they made when we first became fans. Nobody seems to want to admit when their favorite musician is washed. Stans root for their faves like sports fanatics root for their regional teams (some even have team names, team colors, mascots, and rival teams). There’s this feeling of unwavering loyalty no matter how they perform because of the forced parasociality, or in this case years of devotion, making stans feel like they’re locked in no matter what.

I often think of the TikTok trend where a voice off camera asks someone if they’re a Nicki [Minaj] fan which immediately activates the person to recite her iconic verses as they run towards the camera person ferociously. While I’m sure it’s meant to be an exaggerated way to show their love for the rapper, this is fully how Barbz, and the stans of many other artists (Swifties, Beyhive, Selenators, ARMY, etc.) act in defense of their idols online. Every fanbase seems to have their own militia that camps out in the comments of their artists’ competitors to tear them down anytime they release a new project. They also often use their own accounts to run unpaid campaigns to make sure everyone is streaming and contributing to their fave’s numbers.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

On the flip side, there are many calls to separate the art from the artist, particularly whenever there are widespread appeals to cancel someone really talented for taboo actions or bigoted remarks, (Claire Dederer’s book Monster: A Fan’s Dilemma explores the complexity of this exact issue). And while as an argument it feels flimsy at best, and irresponsible at worst, to continue to platform anyone who displays high levels of moral bankruptcy, many of us (myself included) have a few Voldemort-esque artists (people who shall not be named — but not him) lingering in our saved songs. I admit that it’s morally gray to pray that Spotify doesn’t unwrap any of my secrets at the end of the year, but being able to recognize that someone whose art we admire should not be deified, even if we can’t get their songs from their unproblematic eras out of our heads, feels a little bit closer to the relationship we should have with celebrities. Or maybe it’s still fucked up. But let ye who doesn’t have a single Azealia Banks song saved cast the first stone.

If you’re old enough to remember the “Leave Britney alone!” video, it feels like one of the earliest viral displays of super-fandom of a musician online. While at the time many of us were oblivious to the financial abuse Britney Spears was facing at the hands of her family, Cara Cunningham, the creator of the video, had her finger on the pulse, encouraging us to show compassion towards Britney in the midst of her mental health crisis. Even though it felt melodramatic to be driven to tears over Britney’s media treatment (poor thing probably has some strong water placements), the “#Free Britney” movement that followed years later showed the value in her call to action over a woman who had zero control over her fortune or fame. Dare I say that, in moments like this, having adoring fans to remind the world that these celebrities are human feels like a benevolent use of a parasocial relationship. But where do we draw the line?

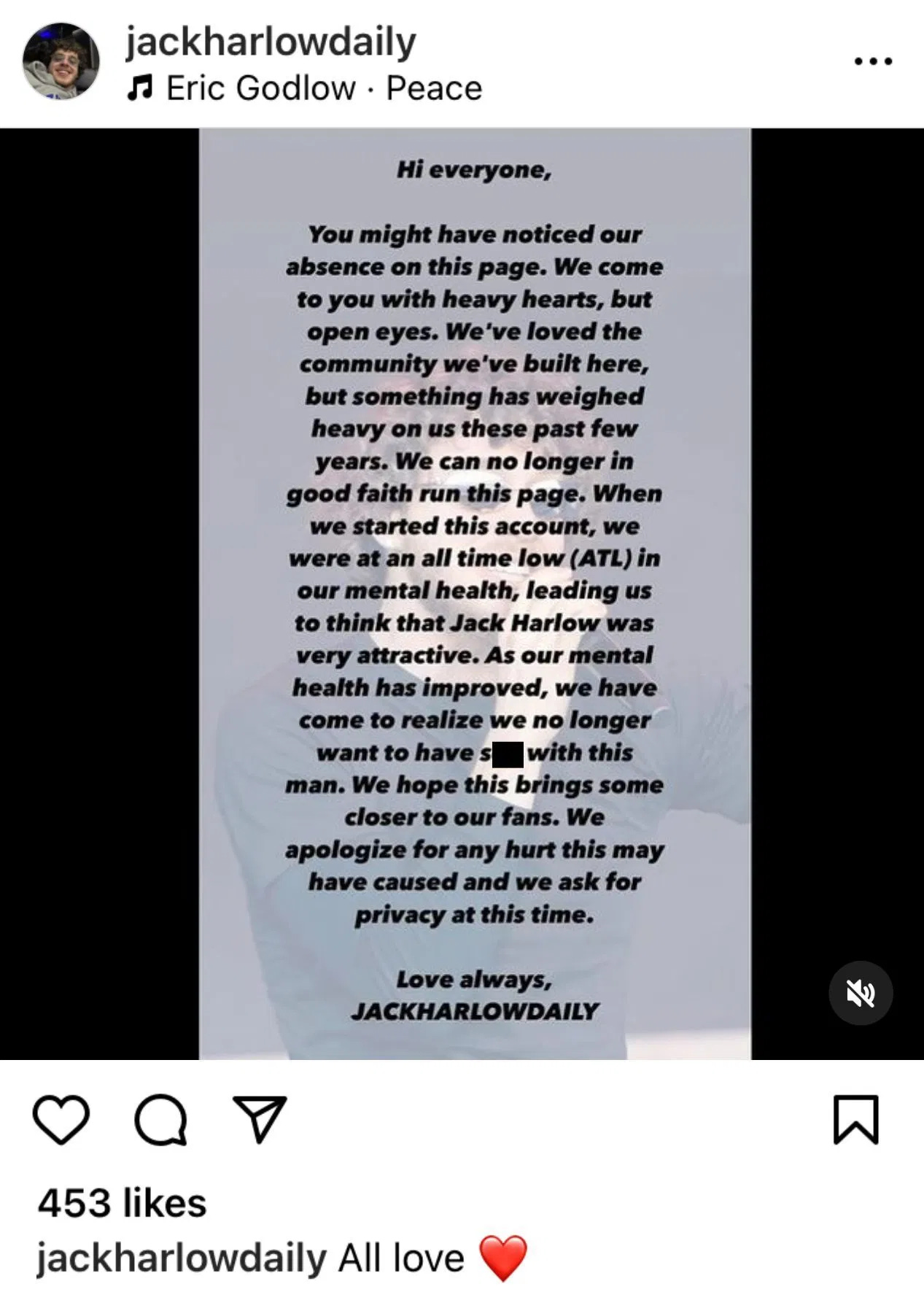

The first public un-stanning that I ever became aware of was that of the creators behind a Jack Harlow fan account. They published an Instagram story to announce that they “no longer want to have sex with this man.” I can’t pretend that it’s not completely unhinged to base your love for an artist solely on whether you think they’re sexy enough for your delusional fantasies, but they gave me hope that more and more people will realize that you’re allowed to have limits.

Whatever the reason — she’s not an untouchable singer or actress, you just miss her old relationship, a certain pop girly and a certain rap girly are not writing as well as they used to (i.e. “CANCELLED!” and “Big Foot”), whatshisname has been exposed too many times as an abuser — you don’t have to stay on this ride! In fact, it’s time to hop off. Even if your fave hasn’t become problematic (yet), the way we worship them has. No wonder Doja Cat cursed out her fans two years ago and even encouraged deactivations of her stans’ accounts.

I’m begging you: Delete or unfollow stan accounts. Put down the pen, or in this case, phone, Stan. We’ve lost the plot completely. Your hero worship only serves to enable wealthy corrupt artists to continue to be corrupt while becoming more wealthy. You maintain a one-sided relationship that doesn’t move the cultural needle and therefore does not serve you. What would happen if these artists solely had to depend on the quality of their art and an ambiguous or unproblematic persona rather than their congregations’ cult-like steadfastness in order to sell us something?

Certainly not The Life of a Showgirl.

Catherine Mhloyi (she/her) is a Brooklyn-based social editor and producer at Them and a culture writer whose work has been published by Them and Teen Vogue.