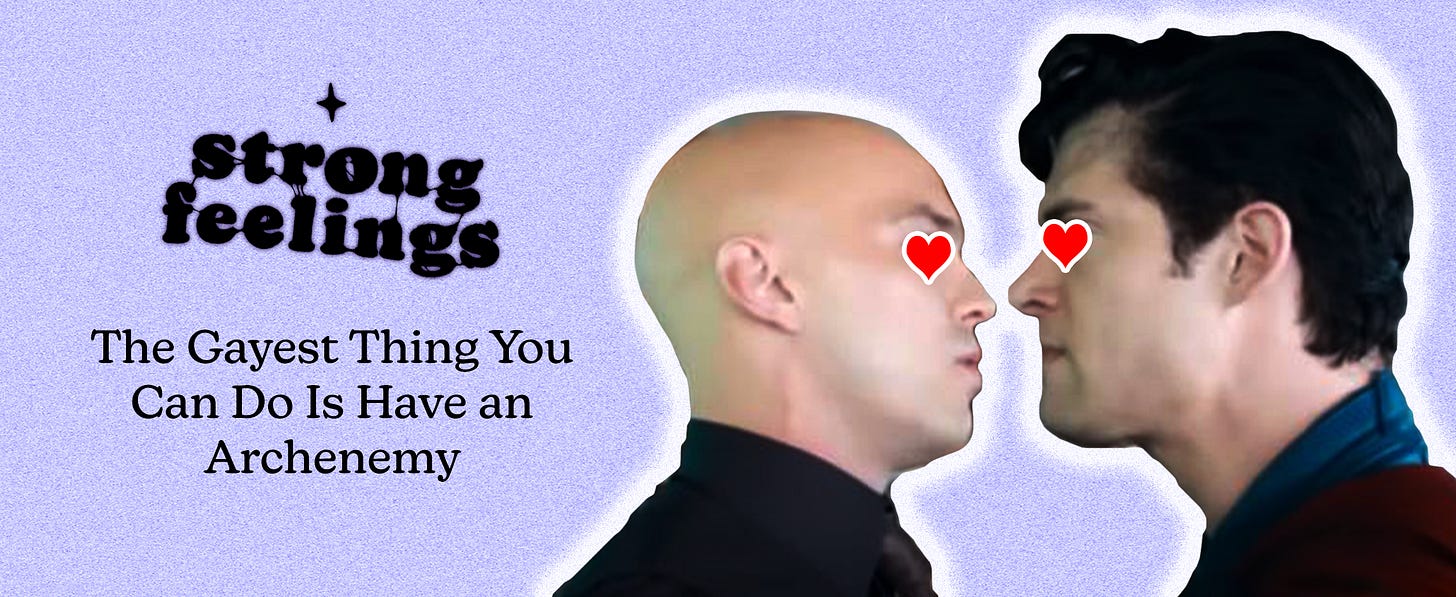

The Gayest Thing You Can Do Is Have an Archenemy

welcome to strong feelings! Essays by writers we love, in which they share their most impassioned opinions on a given subject. In today’s strong feelings, writer AJ Mason explores blurry lines between love and hate and the long history of queer-coding archenemies.

Lex Luthor seems to consistently use his intellectual prowess, scientific access, and privilege to do one thing: have a son with Superman. This has been occurring since the ‘90s, when Conner Kent (aka Superboy) was first introduced to the comics, and then most recently with Ultraman in James Gunn’s Superman this year. Often stealing DNA samples from Superman during combat and mixing in his own to “fill in the gaps”, Lex seems to desperately claw at the right to reproduce with his so-called archenemy, even referring to Superboy as his son in some iterations. Though Lex is generally defined as Clark’s biggest hater, looking closer reveals something much more complex: a pining desire and admiration for Superman that feels decidedly queer in nature, with even the requisite LL initials to match the rest of Superman’s love interests (Lois Lane, Lana Lang, etc.).

There’s a layer of eroticism — an air of intimacy — that comes with nemesis pairings like this. The undercurrent of obsession that serves as the foundation for most rivalries, and the way they experience each other at their most stripped bare and raw, seems to move characters and audiences alike; hence the craving for enemies-to-lovers tropes. The intensity of this dynamic is arguably best exhibited in comics, filled with superhero settings primed for lifelong archenemy romances that connect multiple generations of queer kids searching for any representation they can salvage. When this lens is used to read relationships like Deathnote’s star-crossed manga “boyfriends” Light and L, X-Men’s Professor X and Magneto and their on-and-off again “friendship”, Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s Buffy and Faith steamy rivalry and, of course, Lex Luthor and Superman – we open ourselves to a deeply queer reading.

In setting the stage for our right to read Lex and Superman as a story of queer yearning, we have to take it back to the 1930s. Censoring of queer stories in media is foundational to the birth of multiple artistic mediums, with guidelines like the Hays Code (1934-1968) preventing depictions of queerness in film. During the 1950s, the Lavender Scare era depicted queer folks as a national security threat, perfectly setting the stage for a different moral panic focused entirely on comics. The 1954 release of American psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent heavily contributed to the comic panic, as he alleged that comic books were harmful, violent, and caused juvenile delinquency. Wertham even specifically critiqued what he considered to be queer subtext in characters like Wonder Woman and Batman. Since comics were seen as literature for children, parents around the US campaigned for censorship.

In 1954, the Comics Association of America was formed in response to the massive public outcry against the violence, horror, and supposed queer imagery in comic books. Its magistrate, Charles F. Murphy, established the Comics Code Authority (CCA), which intentionally resembled the Hays Code and placed huge restrictions on comics, establishing many story staples we’re accustomed to today like superheroes’ ‘no-kill’ rules or the ‘good guys’ always triumphing. Mirroring the Hays Code, the CCA also strictly forbade the depiction of “sexual perversion or any inference to it”, which was understood to include queerness of any kind. Though the CCA was technically “voluntary”, publishers truthfully had no choice but to abide by it when the population was staging public book burnings and various cities issued comics bans; not to mention the de facto enforcement from comic distributors who refused to carry comics that lacked the CCA stamp of approval.

All of this created the framework for how queerness would be portrayed in media, such as queer aesthetics being associated with evil characters that should be punished. This association of queerness with villains makes reading nemesis pairings as queer that much more reasonable. It also meant that when writers wanted to include queerness, they had to do their best to work around the ‘sexual perversion’ rule, setting the stage for queer-coded characters in comics: characters who aren’t clearly declared queer, but whose mannerisms, habits and actions indicate the presence of queer subtext.

While some may attempt to relegate queer coding and subtext to wishful gay thinking, writers like Chris Claremont, who wrote on the Uncanny X-men from 1975 to 1991, have confirmed that there absolutely were characters intended to be queer. Claremont discussed in various interviews that his original intent for X-Men characters Mystique and Destiny was not only for the pair to be a couple, but for Nightcrawler to be their biological child. Although his pitch was refused 40 years ago, in 2023 it was finally retconned (the act of revising an existing fictional narrative by introducing new information post-publishing) into X-men canon. There are other examples as well, such as Claremont’s declaration on fan podcast Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men that his intent for Kitty Pryde and Rachel Summers was for the duo to be love interests.

Even in an attempt to stamp out queer media, our stories have a way of being told. Whether it was ‘80s Destiny & Mystique’s mainstream-coded romance or thriving underground comics that allowed actual queer writers to depict our lives like Alison Bechdel’s Dykes To Watch Out For (1983-2008), we’ve always been here. This reality also gives us the license to explore the queerness of countless relationships through a deeper and more subtext-focused lens, because we know that lens is not only historically supported, but necessary. An ability to read and write queer subtext, to provide representation even when we can only do so quietly, to take our right to be represented even in characters straight society holds most dear, are necessary tools during mass moral panics like the one we’re barreling towards now.

For many queer kids, comics were — and are — a safe haven; not only because of these queer and queer-coded couples, but because of the innate queerness many of these stories carry. From Superman to X-men, many comics tell tales of oppression, isolation and social prejudice that resonated with us. Even further, the rejection of normative ideas around romance, sex, and sexuality that comes from incorporating beings and characters from all over space and time has a queer undertone. Alien/human relationships that fundamentally disrupt how we think of sexuality, shape-shifting creatures who render our understandings of gender moot, and characters from various dimensions and cultures with different romantic norms made us feel like we fit in easily.

In reading archenemies from a queer lens in particular, their passion and intensity coupled with fear and frustration can feel rather familiar for queer folks. These similarities between love and hate that feel perfectly exemplified through archenemy pairings aren’t just fictional, but actually have scientific backing. Neurobiologist Semir Zeki of University College London studied the patterns of brain activity stimulated by both hatred and love, finding that there are two areas that show notable stimulation under both scenarios. The neurological overlap between these emotions can help explain characters like Lex Luthor. What could be seen as a misplacement of his desire for Superman and an inability to identify it, resulting in his obsessive desire to clone and in some readings, procreate, with his archnemesis. It then gets confused as hatred or jealousy instead, something many queer folks have experienced. In a society telling you that you simply cannot, and should not, feel queer affection, many of us moved our unyielding fascination, our clinginess or preoccupation, with a crush that simply couldn’t be into the only other emotion we’re taught can justify that obsession: hate.

The specific areas of the brain that are stimulated by both love and hate are the putamen, heavily tied to motor skills, and the insula, which performs a variety of functions but the most relevant for this context is its suspected involvement in responding to emotionally distressing stimuli. In love, the insula can be stimulated by the fear of loss or absence of a partner, while in hate it may be due to feeling frustrated at someone’s presence. Receiving constant societal messaging that there is something innately wrong with queer desire means that we’re likely feeling both versions of this stimulus simultaneously; we may fear the loss of our object of desire just as much as we are also frustrated by their presence and what it requires us to acknowledge. Lex’s discomfort with Superman’s very existence, his belief that Superman is an abomination he must be rid of, reminds me of the first time the mere presence of a woman forced me to confront my queerness. Growing up in the deep south, and then the midwest, I couldn’t have been less comfortable with those feelings – and I absolutely wanted her to disappear and rid me of them, to free me.

This coincides with another aspect of Zeki’s research as well: that love actually deactivates the parts of the brain linked to judgement and reasoning, while they remain intact in hatred. For queer folks, we aren’t afforded the luxury of acting on our desires without rational thought; our homophobic world requires that we remain rational out of survival, potentially making it difficult to lean into the full neurological experience of love in the brain and making it even easier to mistake our feelings for the staunch rationality of hatred. Lex exemplifies this perfectly in his extremely calculated and strategic behavior towards Superman, leaning on his intellect to distance himself from feelings of affection.

This muddying of feelings, this mix up of obsession and childish possessiveness, of confusion birthing disdain, doesn’t just make Lex’s habits surprisingly relatable, but the habits of countless other nemesis pairings can be seen this way as well. For some, it’s the oozing sex appeal of resident DC hot-boy Nightwing and his enemy Deathstroke, for others it’s Wonder Woman and Cheetah or Storm and Callisto — all of which have strong queer-coded cases. Live action shows like Buffy and Faith in Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Xena and Callisto in Xena the Warrior Princess can’t be forgotten either, with their cult queer followings.

While readings of villains like Lex or Callisto as queer are certainly imperfect, and there’s a valid critique of the history that portrays us in this light, it doesn’t mean that no aspect of it may resonate with those reading it – because many of our own experiences are imperfect as well. Ultimately, from even the worst of conditions we’ve found ways to see ourselves in these stories; hell, we’ve built communities around it. We write fanfiction and interpret, and we have every right to, because who could better understand the pain of a desire that cannot be realized, and the fight to do it anyway, more than us?

As we dive headfirst into yet another frenzy of reigniting “traditional” values, writers and artists will still work to create queer stories and these techniques will be all the more important. While reading into Lex and Superman’s relationship, or any other duo’s, might be all fun and games, it also taps into a powerful ability to will our stories into existence.

AJ Mason (@ajvstheeworld) is a writer and creative, based in Brooklyn, NY. AJ’s writing attempts to contextualize smaller moments within our larger culture, weaving connections between history, art and politics. Alongside writing for publications like Them and Autostraddle, AJ is either putting their philosophy degree to use (finally!) in essays on their Substack or conducting deep dives into their favorite animated shows on TikTok!

great https://kaliscan.site

Lex was trynna have Supes’ Baby!!!!!! Through IVF?!?

Sounds like a plot line in Queer As Folk