why are all the witches talking about gatekeeping on TikTok?

welcome to strong feelings! Essays by writers we love, in which they share their most impassioned opinions on a given subject. In today’s strong feelings, writer Heather Akumiah, who recently published her debut novel Bad Witches, explores the chaotic world of "gatekeeping" on WitchTok.

Some people online want to bring back gatekeeping. This is a quintessentially hot take, as it goes against everything the internet has been telling us for the past five years or so: that gatekeeping is a grave, immoral crime. Laura Harrier worked hard on her style, and wants to keep it to herself, thank you very much. Lizzo sees the spread of AAVE to non-Black audiences as an opportunity for the masses to critique Black culture. These are, to my ear, reasonable and increasingly common takes, but a search of “gatekeeping” on TikTok still brings up a mix of pro- and anti- rants on the subject.

Nowhere is the belief in gatekeeping stronger, though, than on WitchTok, a community that is built on conflicting tenets of sacredness and universality, and that found itself in the center of a gatekeeping dust-up a few weeks ago (not their first). I came across WitchTok in July, when I was researching modern witches in preparation for the release of my new novel, and ended up discovering a very spicy debate in action.

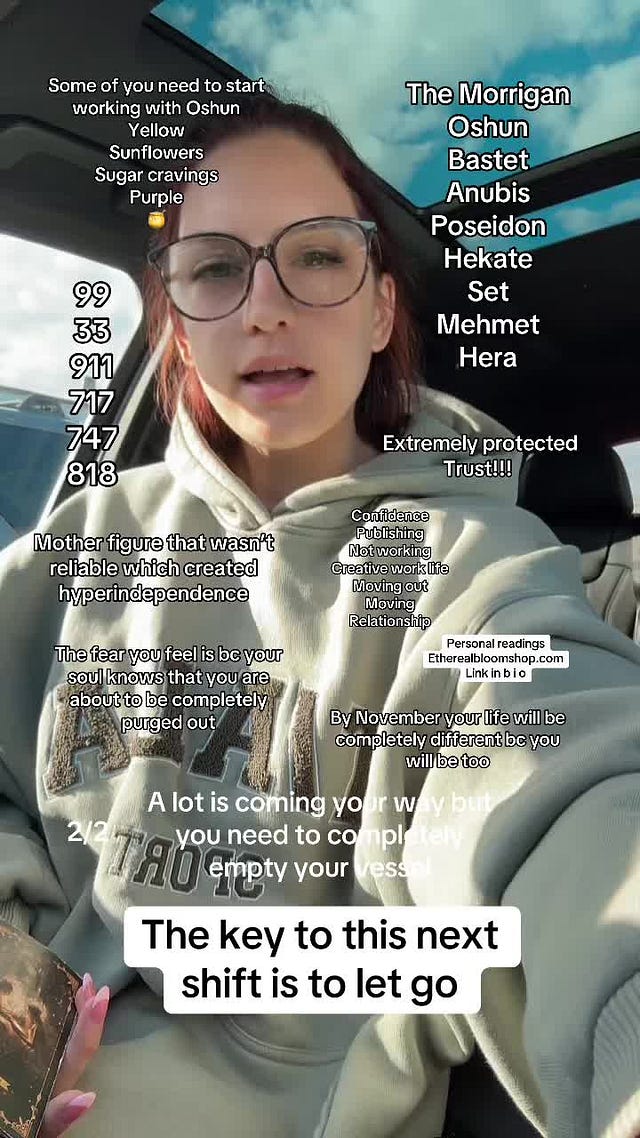

It all started when a witch named Sarah posted a TikTok in which she claimed to be channeling Oshun, a spirit that is central to a range of Yoruba and Yoruba-based spiritual traditions, like Orisa, Isese, Hoodoo, and Santeria. These traditions are, like other religions and belief systems, a complex web of legends, myths, rites, rituals, symbols, deities, and codes that aim to explain human existence. According to Sarah, Oshun wanted to remind Sarah’s 170k followers that they were being mothered and taken care of by the spirit, and that they could give their worries over to the universe. It wasn’t Sarah’s first time claiming to channel Oshun, but this particular video garnered much more attention than earlier ones.

Sarah’s followers seemed understandably comforted by the message of her video, but her fellow WitchTokkers were immediately suspicious, criticizing Sarah in her comments and in their own reaction videos, in which they advocated for gatekeeping African spiritual practices. Some pointed out that Oshun can’t be summoned by tarot. Others noted that Sarah, by her own admission, wasn’t an initiated priestess. That Oshun, as Sarah presented her, sounded suspiciously like a Sunday-service pastor. Crucially, Sarah is white, which just makes it kind of unlikely that she had a legitimate connection to West African spiritual traditions.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

It turns out WitchTok had discussed this exact issue many times before and come to the same conclusion. “Witch” is a broad identity that describes people who believe in and conduct practices in service of a range of occult beliefs. This means anyone from a self-taught tarot reader to a third generation Vodou priestess can call herself a witch. But the Yoruba practices with which Oshun is associated are closed practices — they differ from other spiritual traditions in that they can’t be accessed without training.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

While there are some disagreements about the details, it’s widely agreed that practitioners of Yoruba-based spiritual traditions (who, in addition to calling themselves practitioners, identify as witches, conjurers, brujas, priests, priestesses, and diviners, among other things) require initiation to assume their titles. Initiation is a semi-formal education that includes mentorship from an established practitioner, ceremonies that often entail international travel, and a number of other rituals I won’t claim to understand, lest I end up like Sarah. An ancestral link is also important, though not strictly necessary, for gaining spiritual abilities — like the ability to communicate with Oshun. I know this because the witches of TikTok weren’t shy in imparting this information to Sarah.

Honestly, I was thrilled by the spectacle of these response videos. In an internet landscape that mostly champions subjective truths, there was something intoxicating about a bunch of people telling another that she wasn’t actually doing whatever it was she thought she was doing. That they, through their superior training, education, and perspective, could unilaterally dictate her reality.

I spoke to Black WitchTokkers who ran the gamut from amusement to outrage over Sarah’s claims about Oshun. They were quick to point out that Sarah’s treading into Yoruba religions without training was motivated by the same arrogance that characterizes white people’s interactions with other, non-spiritual elements of Black culture. Even if she was acting out of admiration, her flouting of rules betrayed a deep(ly white) condescension, a belief that there are no subjects she can’t understand. But it’s not just witches from marginalized communities who advocated gatekeeping. One witch I spoke with, Cece, a self-taught practitioner who works with “energy” and learned by “follow[ing] her intuition” —AKA the furthest thing from a closed practice—told me point-blank, “Honestly, I feel like all witches should gatekeep their work.” Her reasoning was that witchcraft is personal, that what works for one witch won’t necessarily work for another. She didn’t sound too different from Laura Harrier talking about her personal style.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

When I asked these witches how they felt about gatekeeping, whether they thought it was wrong or unfair, they seemed confused by my question. I received responses like “not everything is for everyone” and “some things have rules.” Only one witch I spoke with, Angelea, had anything negative to say about gatekeeping. Despite spending much of our interview emphasizing the importance of respecting the rules of closed practices, she railed against gatekeeping. “Gatekeeping is misplaced personal power,” she told me. Wow, I thought as I typed this into my notes. That’s a bar. According to Angelea, gatekeeping is something you do to make yourself feel a little more powerful, to ensure another person doesn’t catch up to you. She went on to explain that gatekeeping is also elitism, and that some closed practices are actually a response to the gatekeeping enacted by colonialism. “Colonialism gatekept witchcraft?” I asked her. Yes, she explained, colonialism gatekept spirituality, the knowledge that humans are more than just their bodies and that we’re all connected to the divine. I typed harder, thinking of divine right, predestination, civilizing missions — this woman was a genius.

We hung up, I closed my laptop, I took some time off the project. When I came back to look at my notes, I was honestly kind of confused. How was I going to wrangle all these ideas into a single piece? How did we get from individual power to colonialism, a system that, famously, is made possible by the collusion of many? In what world does a cliquey TikTok witch deserve the same judgment as a 16th-century Spanish friar?

Everything Angelea said had the ring of truth, but only in isolation. But this wasn’t Angelea’s fault — her move from personal power to colonialism was simply a reflection of the enormous breadth the word gatekeeping has right now. Before gatekeeping became one of the internet’s favorite words, I remember associating it strongly with academia; Twitter intellectuals were always complaining about gatekeeping in PhD programs. The Cambridge dictionary (lol) confirms this association, defining “gatekeep” as follows: “to try to control who gets particular resources, power, or opportunities, and who does not.” The gatekeeper has power and authority; the gatekeepee does not.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

These definitions are, of course, different from what gatekeeping means now (they’re different, even, from the 1943 definition originated by Kurt Lewin). At some point in the last five years, the word gatekeep underwent the semantic shift that has kicked the life out of so many once-useful words. Gaslighting is lying. Trauma is a bad experience. Gatekeeping is keeping anything to yourself. These transformations are tragic not because they’ve made these terms more popular, or because they’re technically wrong, or even because they’ve made these words less specific. What’s worrying really is the shifts have been so fast as to be lopsided—the words have kept their solemn associations but none of the details that help explain that solemnity.

Which is why the take that we should bring back gatekeeping can be popular and contrarian at the same time—because no one knows what the hell we’re talking about. No one wants to gatekeep (bad, grave, immoral), but everyone wants the right to keep details about their favorite pizza shop to themselves (normal, only mildly ungenerous, not really gatekeeping at all). And it’s why all these witches found my line of questioning confusing, even stupid. If you return to the original definition of gatekeeping, the definition that earns its moral weight, there’s not that much to argue about. You can’t gatekeep from the margins, so no, these Black witches aren’t gatekeeping Sarah (or gatekeeping Oshun? See, I’m losing my footing). An individual witch can’t gatekeep her personal practices from another. There are arguments to be made about the power of an influencer who doesn’t share where she got her outfit, but it’s not an influencer’s shirt you’re really after; it’s the more shadowy, intractable elements of her success: the family money that’s enabled her to pursue her career, the commercially palatable looks that make her popular, etcetera. In that way, maybe it’s more accurate to say that accusations of gatekeeping are misplaced personal powerlessness.

When I started writing this piece, I thought I’d be trying to convince you, with the backing of indignant witches, that anything valuable needs to be cordoned off; that communities perpetually under siege have no choice but to close ranks; that, if everyone got to be a Plastic, then no one would be a Plastic. Basically, I thought I’d be arguing that gatekeeping is good and necessary. But, actually, everyone already agrees with me. The girls are fighting only because we don’t know what the word gatekeeping even means anymore. Maybe I should be arguing that we bring back specificity or that we should be gatekeeping words like gatekeeping. But, the internet being what it is, that seems unlikely. Until we find a way to shut the internet off or slow the whole thing down, writers like me will simply have to give you 1,500 words when we could’ve just given you one.

Heather Akumiah is a writer based in New York. She is the author of Bad Witches and co-host of the Limousine reading series and podcast.

This was really an excellent read, thanks for not “gatekeeping” the nuance of your reporting/thinking

This kills! My favorite example of the same phenom is "toxic." "Toxic," in the field of chemistry, is pretty specific. The contemporary meaning has been diluted through misuse.

If I caught one of the new meanings of "gatekeeping," it would be what we fogies call self-censorship. I write without disclosing some details to protect myself and others.

As for the more old-school meaning of gatekeeping, I agree with you and the others you've written about. It's really about control of others' efforts to present in public. That definition is not too hard to understand if one cares to do a teensy bit of research.

And that's just it. We still have a cultural presupposition of authority when we encounter video, audio, and text content now widely available online. We hold that belief because when we fogies were young, there were gatekeepers everywhere. Culturally, we have not broken out of that paradigm.