A Deep Dive Into the Connective Power of the Public Restroom

The unique thrill of bathroom camaraderie at Bad Bunny’s historic “No Me Quiero Ir de Aquí” residency.

welcome to strong feelings! Essays by writers we love, in which they share their most impassioned opinions on a given subject. In today’s strong feelings, writer & comedian Tess Garcia explores the deeply connective power of the women’s public restroom, as seen in her most recent trip to Bad Bunny’s residency in Puerto Rico.

One Friday night in August, I stood in a crowd of women and femmes at El Coliseo in San Juan, Puerto Rico. We arrived in pursuit of Bad Bunny’s historic “No Me Quiero Ir de Aquí” residency, donning crochet dresses and sets inspired by his latest album, DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS. With hours before the show kicked off, we weren’t in our seats. Nor were we waiting in line for merch, or even for a Benito-themed cocktail. This group of concertgoers, singing and dancing to reggaetón classics that blared across El Choli, was having the time of our lives in the bathroom.

“I guess I’ve never been in a men’s bathroom, but I don’t think they use that as a sacred space in the way that we do,” said Nora Princiotti, cohost of The Ringer’s Every Single Album podcast and author of Hit Girls, a deep dive into the world of 2000s popstars. “It’s the portal to girl world.”

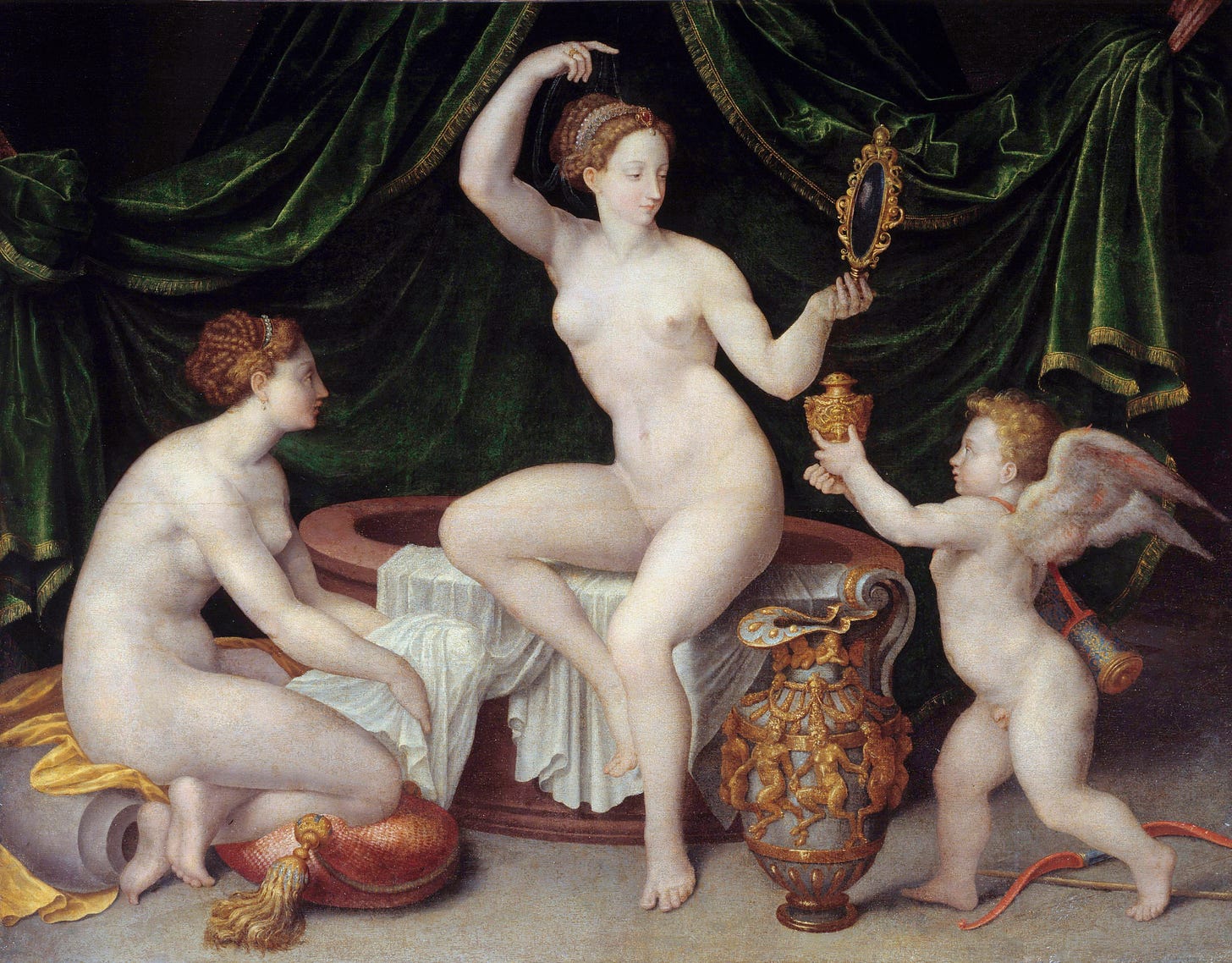

Public restrooms are highly politicized spaces that connote belief systems as easily as bodily functions. At worst, they’re weaponized in the persecution of trans people. At best, they offer fertile ground for kinship among women and femme-identifying folks. According to Bloomberg, America’s first public bathrooms emerged in the mid 19th century, but for decades prior, white, middle class women congregated in public “lounges.” These gender-segregated rooms were found in hotels and department stores, and reinforced the belief that women should lead private lives, even when outside the home.

When indoor plumbing came around, the women’s lounge was factored into the creation of the earliest public bathrooms. The concept of gendered, multi-stall bathrooms — a thoroughly outdated formula by today’s standards — is in part thanks to the work of the architect Isaiah Rogers, who couldn’t have known his design would set the stage for one of the most unique, yet universally recognized forms of community-building among women.

I grew up on early aughts pop culture, which transfixed me with its portrayal of bathrooms as connective tissue between female friends and strangers. The Amanda Show might not have aged well, but it gave us The Girls’ Room, a recurring sketch about four high schoolers who used sinks, mirrors, and automatic hand dryers as the backdrop for their antics. The girls’ personalities couldn’t have been more different, but they developed a bond in this siloed space, away from the social hierarchies of classrooms and cafeterias.

In 2025, bathroom bonding is associated with vulnerability. Nothing strips you down to your humanity like waiting in line to pee. Even celebrities aren’t immune. Consider the annual Met Gala bathroom selfie, which gives onlookers a rare peek into fashion’s biggest night, or Taylor Swift’s “All Too Well (10 Minute Version),” which reveals an emotional encounter in an awards show bathroom (“Not weeping in a party bathroom, some actress asking me what happened). Few of these now-viral pop cultural moments could have taken place without the centuries-ingrained “lounge” culture of the space. “Either you go to the bathroom for this moment of euphoria, like, 'oh my God, I met this girl and she’s going to be my best friend and she says I look so hot,” said Princiotti. “Or something went wrong, and the bathroom is where you go to have an absolute meltdown and hopefully be picked up by the community.”

For every depiction of the women’s bathroom as a safe haven, free from the threat of cisgender men, dozens more depict it as a hotbed of drug use. The phenomenon has permeated across mediums since Y2K. As Page Six captured the jaunts of Britney Spears, Paris Hilton, and Lindsay Lohan, Pharrell’s N.E.R.D. released a track called “All the Girls Standing in the Line for the Bathroom.” Now, the glorification of restroom drug use pervades in party-hard projects like Charli XCX’s Brat.

Within this polarizing narrative, the public bathroom remains a unifying force. In the words of Princiotti: “It’s the space that’s adjacent to the party but separate enough that either it brings out a different set of reactions from people, or they go there to tell a secret or take a break, or they go there to do something that they don’t want people to see them doing.”

I have never attended the Met Gala. I’m not a Swiftie. I’ve never seen cocaine in real life. But as an Argentine-American who’s obsessed with pop culture, I’ve found connection with other Latinos through the music of our diaspora. Bad Bunny’s residency was my bathroom bonding Super Bowl.

From the moment I stepped into the bathroom in El Choli, it was clear that Benito’s team anticipated its use as a gathering place — to the extent that they enlisted personal care brand method as a sponsor. The company transformed nearly every bathroom in the arena into a tropical oasis, akin to a colorful speakeasy. Stall doors were draped in decals inspired by Viejo San Juan. Colloquial Puerto Rican affirmations, like “Te ves brutal” (“You look amazing”), danced across the walls. Each sink was equipped with bottles of method’s Island Mist Body Wash and faux plaintains hung from the ceiling in bunches. The space was built for the chitchat, makeup touch-ups, and group photos that turn a bathroom from necessary resource to destination.

I spent five hours in El Choli and used the bathroom six times. The visits were fueled by a desire to witness sisterhood, and my frequent hydration. In my first go round, I realized I was tied to fellow concertgoers by the invisible string of chisme, the Spanish word for gossip. In English, the term has negative connotations, but in Latin American cultures, it often connects more than it divides.

“Unlike American gossip culture hell-bent on talking trash about those who have wronged you with a viciously sharp tongue, chisme is never that serious,” journalist Ana Escalante wrote in a 2022 Glamour article. She added that in Latin America’s earliest indigenous societies, orally-traded legends were treated as currency, akin to other valuable items ripe for trading. By the 18th century, women across cultures used gossip to discuss the social acceptability of their behaviors, a protective measure in a male-dominated world. Put simply, the feminine urge to gossip has centuries-old roots, and the Latina urge to chismear dates back further still.

In the bathroom at El Choli, I watched the magic of chisme transpire in real time. Superfans debated which celebrities would appear in Bad Bunny’s casita, the onstage house whose patio has welcomed Lebron James and Jon Hamm. Others weighed the pros and cons of a post-concert club visit. “Déjame secar las manos” (“Let me dry my hands”), one woman playfully scolded two companions, who demanded to see her current love interest’s Instagram profile before she even finished washing her hands. The women could have been family, friends, or recent acquaintances, but in this intimate, femmes-only setting, those lines were wishfully blurred.

As more guests piled into the arena, its bathrooms morphed into de facto dressing rooms. Long lines created time for women to adjust each other’s bra straps, exchange combs, and smooth out any bunching in the outfits most of us spent months preparing. “Oh, body glitter was a great idea,” one stranger said as she looked me up and down. I’ve carried the high of that compliment with me ever since.

In 2025, environments of such safety and community are near impossible to find, especially for Latinos in the continental United States. In an interview with i-D, Bad Bunny told journalist Suzy Expósito that his choice to avoid the US — in both the residency and his upcoming world tour — was fueled by the Trump administration’s mass deportations. “Latinos and Puerto Ricans of the United States could also travel here, or to any part of the world. But there was the issue of—like, fucking ICE could be outside [my concert].”

Between stalls and sinks, I found myself disarmed by an atmosphere of courtesy and calm, one that couldn’t have existed in even the most liberal US cities. Fans freely spoke Spanish, English, and Spanglish as they exchanged tips on how to capture the best videos of the show. When I lingered in the doorway to eavesdrop, women filed behind me without even asking if I was in line. I overheard an impossible number of polite photo requests, and one “You’re in the background of my photo; is that okay with you?”

Princiotti recalled a similarly surreal experience in the bathroom at Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour. “[Swift] does this whole section in Evermore, where for the song ‘Willow,’ there are these big, glowing orbs,” she said. “Somebody had an orb that was made to look like one of those. We would just pass it back. Everyone’s just passing the orb and doing the dance with the orb. We’re having a seance with the orb.”

Our orb rituals and compliment fests matter. They present rare moments of pure unity for women and femmes who have sacrificed financially, emotionally, or otherwise, all in the name of one perfect night surrounded by like-minded people. On Saturday, September 20, Bad Bunny will round out his residency with “Una Más,” a bonus show that will be livestreamed on Amazon Prime Video. For one final night, El Choli’s bathrooms will be the epicenter of chisme for the Latina diaspora. They may exit the bathroom physically lighter, but they’ll also leave more energized than when they arrived.

Tess Garcia is a Brooklyn-based writer, comedian, and stylist who wears many other hats across media and entertainment. Her written work focuses on fashion, pop culture, social justice, and the intersections of all three.