Screaming, Crying, Throwing up: The Medieval Art of Fandom

To celebrate the launch of The Medievalist, our first print issue, we’re publishing a selection of stories from the magazine, plus a few newsletter-only additions, for all of you wenches to enjoy. First up is our cover story on the medieval art of fandom, written by Katherine Churchill, who holds a Ph.D. in medieval English literature. The Medievalist is available for purchase online, now!

Last summer at the Eras Tour in Stockholm, when Taylor Swift first emerged on the stage of Avicii Arena in her sequined bodysuit, the woman next to me in the standing section burst into tears. She had traveled all the way to Sweden from Canada to see the concert, and to finally behold her idol after such a long journey overwhelmed her. While the crowd roared around us, I was struck how her emotional outpouring was so reminiscent of the medieval pilgrims I’d studied as a medieval scholar, who traveled to distant lands to worship their favorite saints.

You see, since time immemorial, people have been screaming, crying, and throwing up over their faves. Today we swoon over anime characters, Lady Gaga, our K-Pop bias, etc. But many of the hallmarks of fandom — effusive emotion, cults of celebrity, fan fiction, and the proliferation of merch — have synergies with popular Western European literary and religious culture during the period between roughly 800 and 1500. In truth, fandom is as medieval as jousting on feast days and parading around in tights.

If you’re a fan, you probably understand what it’s like to feel overwhelming passion for distant or fictional subjects. That’s something that would have felt familiar to medieval people, too. They famously went gaga for religious figures like Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and other saints in Western Europe, which is my area of research expertise. Pious medieval people would express their love for these icons by literally screaming and crying about their love and devotion. As the scholar Anna Wilson has argued, what scholars call affective piety — a medieval mode of religiosity that involved intense and at times inappropriate emotional responses — resembles modern fans’ outbursts about beloved celebrities, genres, or works.

Take the example Wilson draws on, that of the medieval English autobiographer Margery Kempe. Kempe dictated a book about her life in the fifteenth century, which is how we know that she was a huge Jesus stan. When she thought about Jesus, Kempe “myt not kepe hirself fro krying and roryng” (was not able to keep herself from crying and roaring) in a way that “was so lowde and so wondyrful that it made the pepyl astoynd.” (was so loud and so wonderful that it made the people astounded). To many modern audiences, the effusive religious devotion Kempe describes may seem alarming. But fans, I think, will recognize her outbursts as relatable — a way to express profound love, like barking at K-Pop concerts.

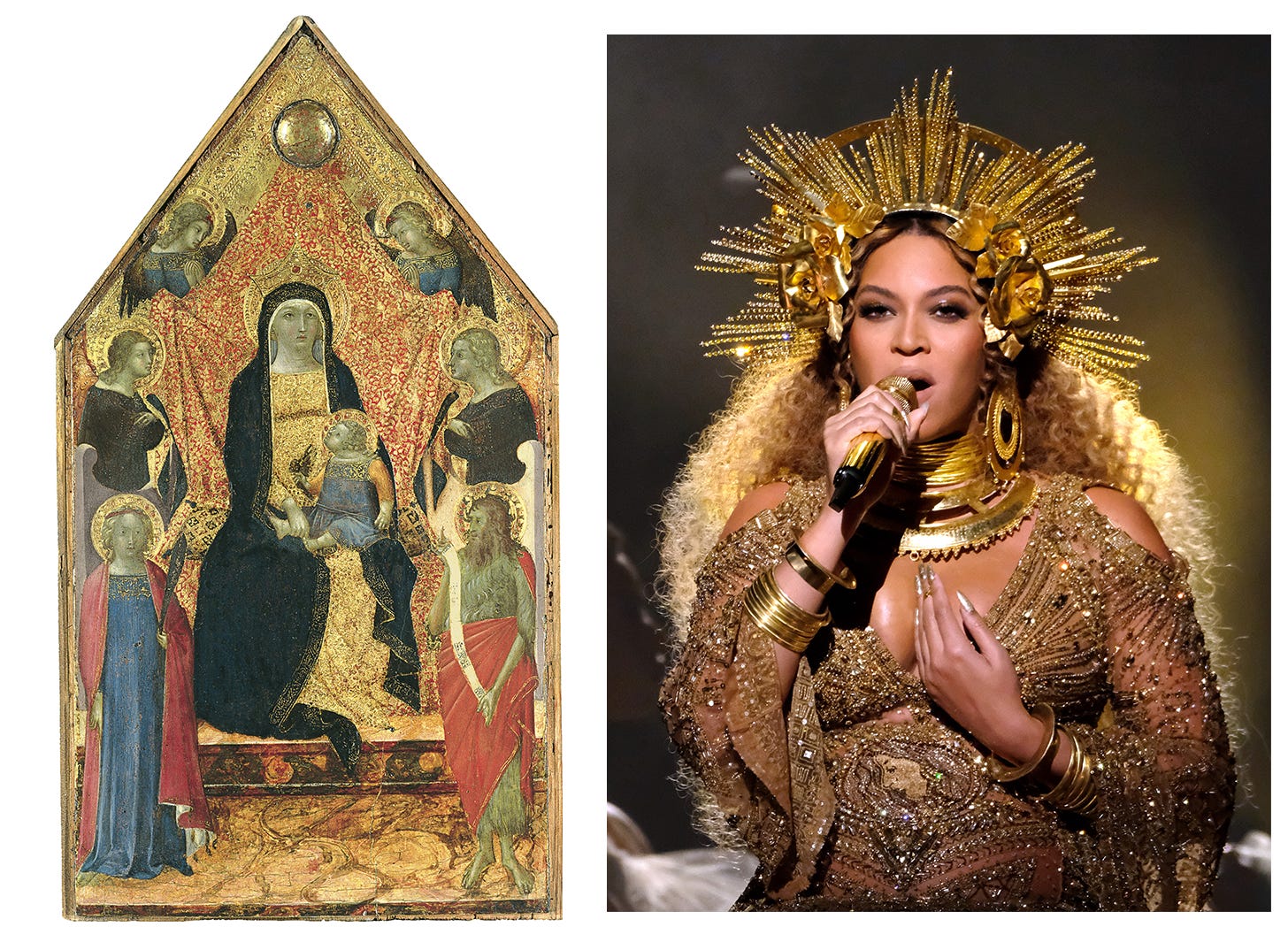

Saints, especially, were adored in the medieval period. The historian Aviad Kleinberg describes them as akin to modern celebrities, in that they were “admired by large enthusiastic crowds,” even though their fans knew “very little about their ‘real’ persons.” I spoke with Maggie Solberg, associate professor of English literature at Bowdoin College and the author of the book Virgin Whore, a study of the biggest saint of all, the outrageously popular Virgin Mary. Towns built statues of Mary in public spaces, and medieval people, Solberg told me, would leave their jewels and clothing to the statues in their wills. Much as we now keep track of celebrities on Deuxmoi, medieval people read and told stories about folks who had visions of Mary and experienced her miracles. Solberg sees both Marian devotion and popstar fandom as forms of goddess worship. “Beyoncé to me is the most Virgin Mary-like one, where everyone acknowledges, like, she is truly flawless.” Medieval people talked about Mary, Solberg said, in a similar way, describing her as “immaculate.” The sense, according to Solberg, is that “she is perfect, but I’m not jealous and I’m not mad, I just love it.”

Like fans who travel great distances to see the graves or the hometowns of their faves, medieval people went on pilgrimage to worship at saints’ “relics” — that is, the preserved remains of their bodies and possessions, including fingers, hair, and clothing. You might take a vacation, for example, for the purpose of seeing St. Thomas Aquinas’s preserved right thumb, or trek across the Pyrenees along the Camino de Santiago to pay tribute to Saint James. Travelers brought home little badges made of hammered metal as souvenirs of these voyages. Shaped like scallop shells, images of saints, birds and other designs, pilgrim’s badges served as proof of religious devotion. Today, mudlarks — people who search rivers in England for artifacts as a hobby — sometimes find these lead trinkets, and many museum collections hold examples of them. Imagine finding an Eras tour friendship bracelet six hundred years from now and giving it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Saint worshippers collected a slew of other devotional objects, too, which we can think of as the medieval equivalent of merch: fashionable brooches featuring St. Margaret emerging from the belly of a dragon, medallions depicting Saint George in full armor. Medieval people carried wooden, glass, or ivory rosary beads strung on silk thread and featuring carved images of the Virgin Mary. Books of Hours, which were popular medieval devotional books used for daily prayer, could be customized to include the stories of the lives of favorite saints, much like the photocards that K-Pop fans now buy, trade, and adorn. These books served as family heirlooms, and were sometimes lavishly decorated, with colorful borders and gold leaf embellishments. Sometimes the images in them are smudged, because medieval fans would actually kiss their pages, as the manuscript scholar Kathryn M. Rudy has discussed in her book Touching Parchment.

Medieval people were also fan-ish in terms of their reading habits. Like fanfic based on fantasy books or manga, medieval literature was “hypertextual” — dependent upon preexisting texts — as the scholar Kasper Bro Larsen puts it in his article in Studia Theologica. Copyright was nonexistent, literary imitation was seen as a form of flattery, and medieval readers relished twists on the same stories and characters. Both fanfic and medieval literature tend to be “transformative,” since they renarrate established narratives, as the scholar Anna Wilson describes in her article in Transformative Works and Cultures.

Arthurian literature, which was popular from about the 11th century onward, is a good example of this taste for the fanfic-adjacent, because many stories have no single credited author, but were rather expanded upon by multiple authors. In addition to quests and battle scenes, the genre is chock full of illicit love affairs that dive more explicitly into the romantic and sexual nature of character relationships — Guinevere sleeping with Lancelot, Sir Gawain kissing Lady Bertilak — that essentially established the romance plot that now underlies modern-day fanfic “with lemon.” Aristocratic medieval audiences across Europe would listen to these stories read or recited aloud at court, eager to hear more about the rotating cast of Knights of the Round Table who reappeared across different authors’ works.

Today we think of religious literature as sacrosanct, but medieval people often fan-fictionalized Bible characters, too. Stephen Hopkins, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia, whose book Translating Hell: Vernacular Theology and Apocrypha in the Medieval North Sea is coming out in 2025, studies the genre called “apocrypha” — spinoff biblical tales that were not a part of the official Church canon — which were immensely popular in the medieval period and essentially bible fanfic. Examples of these writings, which would appear in leather parchment manuscripts alongside other works, might contain unauthorized descriptions of hell or the apocalypse. One particularly popular apocrypha, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, relayed the adventures of Jesus as an elementary schooler as he played with lions and learned to resurrect other children. Of course, there are critical differences between apocrypha and fanfic. “When you are writing Star Trek fanfic,” Hopkins said, “it does not have theological consequences.” But he sees strong similarities too, particularly in the fervent passion they share for stories, their strong “buy-in” from readers, and the way they attest to a “desire for more narrative.” Medieval apocrypha readers, hungry for more Bible stories, sought out texts that filled in the Gospels’ gaps.

Above all, fandom creates community: today, fans gather electronically on subreddits and Discord channels, rally around hashtags, and meet up at conventions. Without the help of cyberspace and air travel, however, medieval people built fandoms the analog way: through word of mouth, quill, and ink.

Several years ago, I came across a stunning piece of verse while researching the thirteenth-century French poem The Life of Saint Euphrosine. The poem narrates the experiences of a saint that the scholar Vanessa Wright has identified as genderqueer; Amy Ogden, the translator of the poem into English, calls it an “invitation to gender transgression.” The poem recounts how Euphrosine was raised as a girl in the city of Alexandria in Egypt, but always felt out of place. On their wedding night, they ran away, changed their name to Esmarade, donned masculine clothing, and began to live as a monk.

At the end of the poem, in a postscript that scholars call an “envoi,” the scribe described their excitement after encountering the story in a library book. “Inspired by love for you [Esmarade] I have rewritten it in French,” they wrote, addressing their beloved saint, “Because I want it to be heard by more people. If someone else joins me in loving you, I will not be in the least jealous. I would like to have the whole world in my company.” Whenever I read those lines, I hold my breath, because the eight-hundred-year-old invitation to share a beloved story feels so urgent and familiar. Celebrating treasured cultural objects and favorite cult figures with others is an ancient practice. So go medieval, fandoms everywhere — it’s historically accurate to be screaming, crying, and throwing up.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece included the word “origins” in the headline. It has since been updated to reflect the original title in the print issue, which was published August 15, 2025: “Screaming, Crying, Throwing Up: The Medieval Art of Fandom.”

*Quotes from The Book of Margery Kempe are from the edition by Lynn Staley. Quotes from The Life of Saint Euphrosine are from the translation by Amy Ogden.

Katherine Churchill holds a Ph.D. in medieval English literature. Her writing has appeared in Time, Defector, Literary Hub, Electric Literature, Oxford American Magazine, and elsewhere. You can find out more about her work via her website, and follow her on Bluesky, @katherinechurchill.bsky.social.

This takes me back to my graduate studies in literature of the Middle Ages. I wrote a paper on courtly love. Talk about worship! A few noble women would be courted by the knights and be made into icons in no time at all. I wish people would worship the eternal, rather than flawed entertainers who are here today and gone tomorrow. At least the fans in the Middle Ages worshipped saints who led worthwhile and, in most cases, very useful lives. These saints gave their allegiance to the Lord, and He doesn't change with the whirling winds of fame and fortune. I very much enjoyed your article as this era seems largely forgotten, but fortunately kept alive by scholars like you.

Beautifully written and incredibly insightful, this essay deserves a much larger audience.